We are sad to announce the passing of our dear colleague, co-founder of IDS and NADS, Robert Louis Jackson, B. E. Bensinger Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Emeritus, at Yale University. He died on Monday, May 2 2022, at the age of 98, with his daughter Kathy present. This is an enormous loss for all of us, for our field, and for NADS and IDS. We are collecting tributes for a memorial post. If you have memories or photos of our wonderful colleague that you would like to share, please use the form linked below.

Share Your Memories and Photos Here

Our memories of Robert Louis Jackson

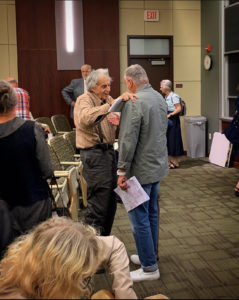

Боб Джексон… Великан и миф. Я не мог поверить, что ему почти сто лет. Он еще в Бостоне в 2019 г. выглядел намного моложе, а в Неаполе, в 2010 г., вообще он был высоким, красивым, нестарым мужчиной. Я собрал здесь несколько фотографий из своих, снятых в Капри в 2010 г. и в Бостоне в 2019 г.

Photos by Graf Aloysky (Stefano Aloe)

Дорогие друзья, мы понесли невосполнимую утрату. Умер один из основателей Международного общества Достоевского, президент Североамериканского (1971-1977) и Международного (1977-1983) обществ Достоевского. Его вклад в изучение Достоевского огромен.

Вечная память!

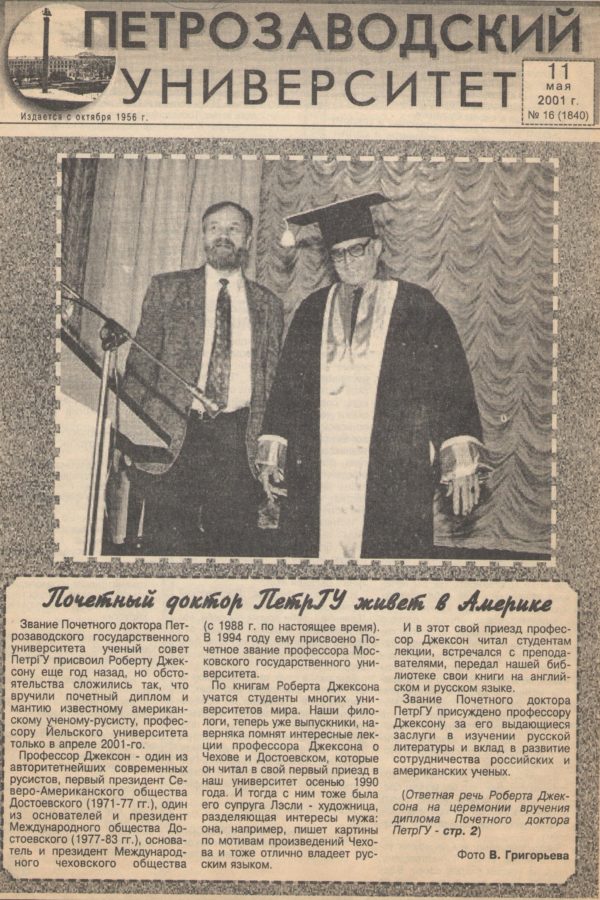

Высылаю два скана. В 2000-2001 годах мы (я и два Боба, Джексон и Белнап) стали готовить в Петрозаводском университете международный центр изучения Достоевского. К тому времени у нас уже были оцифрованы все архивы Достоевского, и мы хотели начать их разработку. Из-за моего переезда в Москву не получилось так, как рассчитывали, но ректор оценил наши предложения, Ученый совет университета отметил заслуги Джексона и Белнапа присуждением звания Почетного доктора ПетрГУ. Два скана рассказывают о чествовании нашего замечательного друга и учителя.

Владимир Захаров

Although it was Caryl Emerson who first publicly supported the translation of Józef Bogusławski’s memoirs at AATSEEL (2002), Robert Louis Jackson was very encouraging about my research on Dostoevsky and the Polish Question to the extent that he shared some of his own findings and offered editing suggestions for the article that I published in Dostoevsky Studies (2006), including the following note: “I’m sure that the materials you have translated will be of interest to readers, especially with a good introduction. And I suggest that write freely about what you think, I mean–not fear to give your own ideas, which I am sure are very interesting.”

Elizabeth Blake

In the spring of 1971 Bob (for some reason I have always called him Bob, although he was most often Robert) taught a graduate Dostoevsky course at Columbia. Taking a course with Bob was an intellectual revelation for me: it was possible to be both scholarly and at the same time to use one’s scholarship to explore questions that were deeply meaningful in a more personal way. The subtitle of his book, The Art of Dostoevsky, captures that revelatory quality that scholarship can occasionally have: Deliriums and Nocturnes. Dostoevsky’s art is indeed one of deliriums and nocturnes, and few critics to this day have rendered Dostoevsky’s work so intensely meaningful as Bob. Always informed by the practice of close reading, his meditative writings on fate, freedom, responsibility, tragedy, memory, vision, beauty, image (“obraz”) and the absence of beauty (“bezobrazie”) have shaped the thinking of subsequent generations of scholars of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Chekhov and others.

His stature in the International Dostoevsky Society (IDS) was simply unrivaled. He would wade into semi-political debates in that complex, passionate, international organization and wade out again, victorious, but somehow miraculously having made no enemies. His gift of creating consensus was extraordinary because it was not born of a hesitancy to disagree and a resort to blandness but rather from an ability to listen deeply and carefully, to listen and to hear, and then to incorporate that other’s point of view into his own. Yes, this sounds like Bakhtin, or even Dostoevsky, but with Bob this was a practice innate to his own personality, not a deliberate philosophy or a conscious ideological practice.

We became friends in the early 1970s, and my husband and I visited him in Truro, on Cape Cod back when his father, Eugene Jackson (who turned out to have been a boyhood hero of my own father-but that’s another story), was a practicing artist in advanced old age. Bob was the son of two important artists and the husband of another, Leslie Gillette Jackson, whose work inspired not only Bob but many of his graduate students and colleagues. His keen visual eye and love of music have suffused and permeated his critical work and have inspired others to allow themselves to also follow a similar path.

For many years Bob organized symposia at Yale to which he invited an ever-broadening circle of graduate students and colleagues. We graduate students-not just from Yale-would find ourselves spending an intimate day with noted Russian scholars, senior Yale professors, and would also get to know graduate students from other institutions. Often Bob would invite several of us to stay at his farmhouse in Guilford. We would sit late into the night with him and Leslie, drinking tea at their very Russian, yet old New England kitchen table.

I continued to visit Bob and enjoyed stimulating intellectual discussions with him up until a couple of weeks before his death. We’d sit at that same table. In mid-April he climbed up the steep stairs to his second floor to find me an article on Goethe’s modernism that he knew would be relevant to my work. Last fall I happened to find the paper I wrote for his graduate seminar-a paper on Notes from Underground, and submitted on May 23, 1971 (my birthday). He wrote, diplomatically, “it’s not easy to pull all this imagery together.” But, he added, that he liked pages 8 and 9! He suggested I turn it into a little article. In November 2021 (50 years later) I did use that old paper as the groundwork for a public lecture. Bob and I had a nice chuckle about that. I was surprised and honored that he asked me to write an introduction for his next book. Yes, Bob has a yet another book about to appear, a very fine study of Chekhov, edited by Cathy Popkin.

Robin Feuer Miller

Дорогие коллеги, с глубокой скорбью узнали весть о кончине дорогого Роберта Джексона. Я, как и все российские исследователи, чрезвычайно опечален этим известием. Мы любили и чтили Роберта Джексона как выдающегося американского слависта, внёсшего, в частности, неоценимый вклад в мировую науку о Достоевском. Будем помнить его всегда.Высылаю несколько фотографий.

Игорь Волгин

Like many people, I can say that Robert Louis Jackson changed my life. His teaching and inspiration were by far the greatest influence on my career. I first encountered his scholarly work when I was a junior in high school and checked out Dostoevsky’s Quest for Form from the Kansas City Public Library. Later, at Yale in 1976, he became my teacher, mentor, and dissertation adviser. I would like to share a memory from a later period. In the spring of 2002, I attended a performance of Chekhov’s Seagull that was the culmination of an undergraduate course taught by Robert and by Murray Biggs of the Yale Theater Department. The play was presented by these young students at the home of Rita Lipson, with minimal costumes and props and with no fancy directorial flourishes. At the end of the play, I found myself weeping uncontrollably, something that had never happened to me at any performance of Chekhov, professional or amateur. Robert later told me that during the course that led up to the performance he had talked more about The Seagull than he ever had in his life. It was clear that the deeply moving nature of the performance was in large part attributable to the profound understanding of Chekhov’s text that Robert had conveyed to these students. His summation of the experience is one that stands for me as an ideal: “It is frightening, for one who has retired from teaching, to realize again how important teaching is for writing! You are forced to think, and to formulate things clearly, and to ask many questions, and to cope with ‘answers’ that raise more questions. And you must do this ‘on time’ — not postpone till next month!” Robert taught me what to strive for as a teacher and a scholar, and in recent years, he has taught me by example how to cope with loss and infirmity with unfailing cheerfulness, kindness, and spiritual vigor.

Susanne Fusso

Photos sent by Toyofusa Kinoshita

If it was not for Robert Louis Jackson, I would not be living on this side of the Atlantic, would not have a tenured position in academia, and would not be a Dostoevsky scholar. I am extraordinarily indebted to his intellect, generosity, and moral clarity in all aspects of my life. I came to the United States for the first time at the end of August 1998, to study with him at Yale. I had won the Henry Fellowship from my undergraduate institution, the University of Cambridge, and had chosen to study at Yale because of Robert, whose wonderful books, particularly Dostoevsky’s Quest for Form: A Study of His Philosophy of Art (1966) and The Art of Dostoevsky: Deliriums and Nocturnes (1981), had inspired me as an undergraduate. Reading Dostoevsky for the first time as an undergraduate, I found the connections between aesthetic and ethical questions contained in both those studies central to my own reading of Dostoevsky’s works. Untangling and elucidating the concepts of obraz and bezobrazie in Dostoevsky’s thought and writings was one of Robert’s greatest contributions to the field and to generations of Dostoevsky scholarship. In that first year at Yale, after which I was supposed to return to Britain, I took a course with him on The Brothers Karamazov, an unforgettable experience. We spent a whole semester reading through the many layers and details of Dostoevsky’s last and greatest novel, yielding revelations that have stayed with me ever since and which still underpin my own reading of the novel. After only a few months, I had decided to apply to the Yale PhD program and to continue my career in the United States. I was also fortunate to take his last course, on Chekhov, before he retired in 2000. During my first couple of years at Yale, he would take me for tea at the Elizabethan Club, a private members’ club founded in 1911 which has an impressive literary collection, including some of Shakespeare’s folios. The club had a rarefied atmosphere and was quintessentially Yale. Our conversations, however, usually revolved around Dostoevsky, and particularly around his Writer’s Diary, which was the topic of my undergraduate thesis and became central to my dissertation. I have fond memories of discussing the scope of my doctoral thesis in the rooms of the Elizabethan club over toast, scones, and tea. Robert agreed to be my dissertation advisor after his retirement, and we continued to meet and connect regularly after he had retired. As I was working on my doctoral thesis and the book it became, the formal questions raised by Robert in Quest for Form and The Art of Dostoevsky continued to inspire and provoke me and they still do to this day. As I read, teach, and study Dostoevsky, I see myself building every day on the foundations I got from reading and studying with Robert Louis Jackson.

Robert’s work on Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and many others, is characterized by interconnected considerations of aesthetics and ethics and a sensitive attunement to form. His readings reflect his own profound humanism, decency, penetrating insight into ethical dilemmas. Skeptical of the pretensions of the literary and critical theory which had begun to dominate the study of literature in the 1980s and 1990s, he was nonetheless attuned to the same philosophical, ethical and formal questions which such theories sought to answer, and he was resistant to being used as an ideological ally in any of the theory wars. His unashamed love for the texts he dealt with did not blind him to the ethical problems with the great Russian subjects he dealt with, and I think he always had a special love for Chekhov, whose quiet humanism was close to Robert’s own.

My career developed in large part thanks to Robert. He invited me to present my first conference paper, on the trial scene in The Brothers Karamazov, for the last of his famous small Yale conferences, on Dostoevsky’s last great novel, a conference filled with famous names, the result of which was the book A New Word on The Brothers Karamazov. He was always generous in introductions for junior scholars like myself, and I met many of the big names of the Slavic field at that first conference. I also have happy memories of my first International Dostoevsky Society conference in Baden-Baden, in the strange time of October 2001, shortly after planes had begun flying over the Atlantic again. He was, as ever, generous at introducing me to Dostoevsky scholars from across the world. I also met and came to know his wonderful wife, Leslie, an artist and intellectual who was Robert’s greatest inspiration. When I finished my dissertation and joined the Yale faculty in 2004, I had the opportunity to interact with Robert and his wife Leslie some more, most notably when I was invited several times to their house in Guilford, an unforgettable oasis of art, culture, and memories with the wall of photos that included Robert’s own photograph of Mikhail Bakhtin, taken shortly before his death. When my husband Ivan and I got together, they had us over, and celebrated our marriage with us shortly before we left for Canada. After we moved to Toronto in 2009, chances to see each other were fewer and far between, but I was overjoyed to see him for the last time in Boston for the International Dostoevsky Society symposium in 2019. Dostoevsky at 200: The Novel in Modernity, a bicentennial essay collection I co-edited with Dr. Katherine Bowers is dedicated to Robert, without whom I would not be a Dostoevsky scholar.

Kate Holland

Photos from William Mills Todd, III

Growing up in Russia, I was always interested in literature (books were the only window on the world that I knew), but never in studying it. Having watched, listened, or read Soviet discussion of authors and texts, and having witnessed, how these authors and texts were instrumentalized in order to expose the deep problems of all previous social systems except the current Soviet one, I wasn’t particularly keen on contributing to this process of spinning, manipulation, and abuse.

My first real awakening had occurred already in New York, when I took Richard Gustafson’s class on Tolstoy in Columbia, and was shocked to discover that studying literature and great authors could actually be a lot of fun. It could be a journey into an unknown, first and foremost. It was Richard Gustafson, who encouraged me to apply to Yale, mentioning Robert Jackson as a great guide for anyone ready to undertake such a journey.

Indeed, I’ve found in Jackson exactly what I needed. For Robert, the authors and their texts were something of absolute value, something you don’t debase by tying it to some sort of exposé of the hidden birthmarks of feudalism, capitalism, sexism, colonialism, or elitism. In Jackson’s treatment, authors’ words and their interaction with other words, have create an amazing symphony, which one can listen to again and again.

Suddenly, the Russian authors, and with them Russian culture, have become an unknown continent waiting to be discovered. What the Soviets and their didactic, schematic, and instrumental approach to literature have taken away, Robert Jackson had managed to bring back. Furthermore, Robert had returned to me the respect for a written word and written documents. Words, used to beguile, spin, condemn, or indoctrinate, became the object of admiration and inexcusable exploration.

While learning a lot from Jackson during our graduate classes, I learned even more serving as his TA for the undergraduate lecture classes.

Once, on the way from the lecture back to the department, I’ve observed Robert smilingly triumphantly. He just spoke to some students and was gleaming from this interaction. “You know, what this student said?” — he asked me. – “He said that they (the students) love my lectures because I am on the side of the author. “

So what? – I asked – aren’t we all? – Not really, answered Robert. –Nowadays, you are supposed to accuse authors in all possible sins, both explicit and implicit.

It suddenly sank in. That’s exactly what I didn’t like about Soviet approach. This “exposure,” this instrumental use of author’s words, this Porfiry Petrovich’s desire to set up a trap and then capture unsuspecting Raskolnikov into a verbal net.

I’ve returned frequently to these words of Robert: “to be on the side of the author.” How simple. Yet, it requires a great mental, emotional, and aesthetic effort. To follow the author with the attention he deserves, to take his words in all their complexity, to let these words to reverberate without drowning their music into outside static.

During his lectures, Robert would frequently pronounce some key word of a text, and then he would let it sing by amplifying and articulating all its hidden melodies and echoes. His genuine excitement of discovery, his joy of both highlighting a keystone term and mapping it within – what he called, using Henry James term–the figure in the carpet, was palpable. And it would infect his audience with the similar exhilaration. Robert’s lectures rarely fail to exhibit this excitement of discovery, which such concepts as joy of reading or pleasure of the text imply. No wonder his audience loved his lectures so much and found his devotion to the great Russian authors and their inexhaustible legacy so irresistible.

Vladimir Golstein

Photos from Kathy Jackson